NHBP Tribal History

An overview of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi historical timeline.

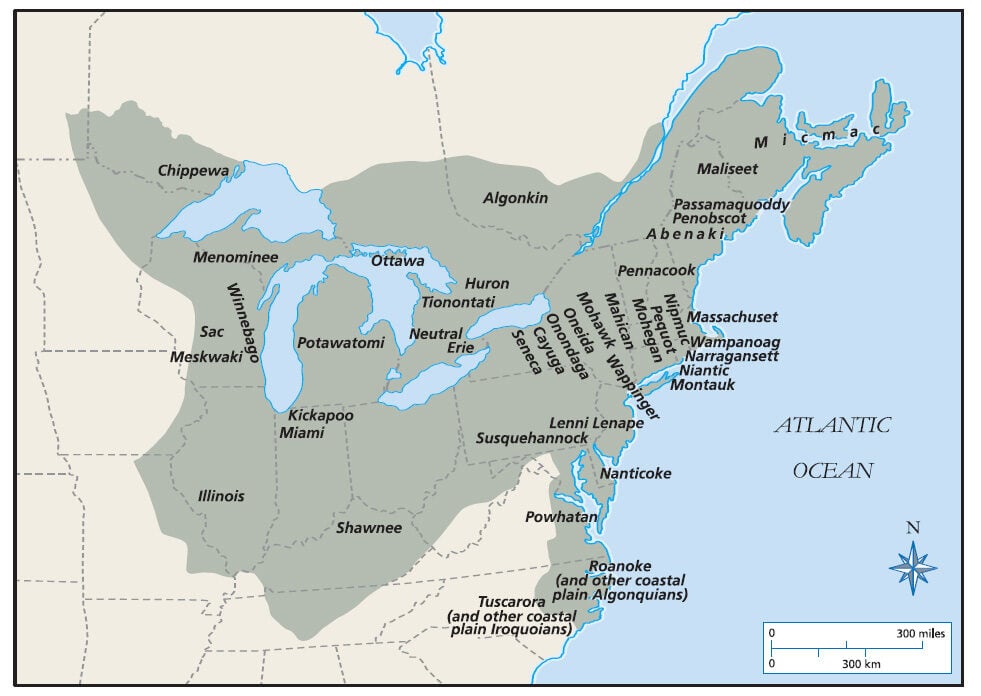

"The Council of Three Fires" forms circa 796 AD

In the early 1500’s, "The Council of Three Fires" split off into three separate groups

A small group of Potawatomi meet the first European

French and Iroquois Wars (a.k.a., "Beaver Wars") Force the Potawatomi to Relocate to Door County, Wisconsin

Great Lakes Algonquin and French Drive Iroquois Back to New York | Potawatomi Migration Back to Michigan

The Potawatomi came to Detroit between the years of 1712 and 1714, temporarily settling between the Wyandot (Huron) and French forts.

The Detroit Potawatomi left their villages on the Detroit River in October 1763 and spread their villages to the south and west, setting up various hunting camps.

Signed August 3rd, 1795, the Treaty of Greenville followed negotiations after the Native American loss at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

The Huron Potawatomi are involved in the signing of the 1807 Treaty of Detroit in which 8 million acres are ceded to the government for roughly 1.2 cents per acre.

The Potawatomi signed the first Treaty of Chicago on August 29th, 1821, ceding much of their remaining land to the U.S. Federal Government. Similar to the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, this treaty impacted the band of Huron Potawatomi. Most settled on a four-mile square tract of land reserved under this 1821 treaty that was known as the “Nottawaseppi Reservation located on the banks of the St. Joseph River in what is now St. Joseph County’s Mendon area.

As part of the Treaty of St. Joseph, signed September 19th, 1827, the Potawatomi ceded to the U.S. Government settlements along the River Rouge and River Raisin in southeast Michigan and areas in southwest Michigan around the Kalamazoo River. The Nottawaseppi Reservation was also enlarged to 99 Sections.

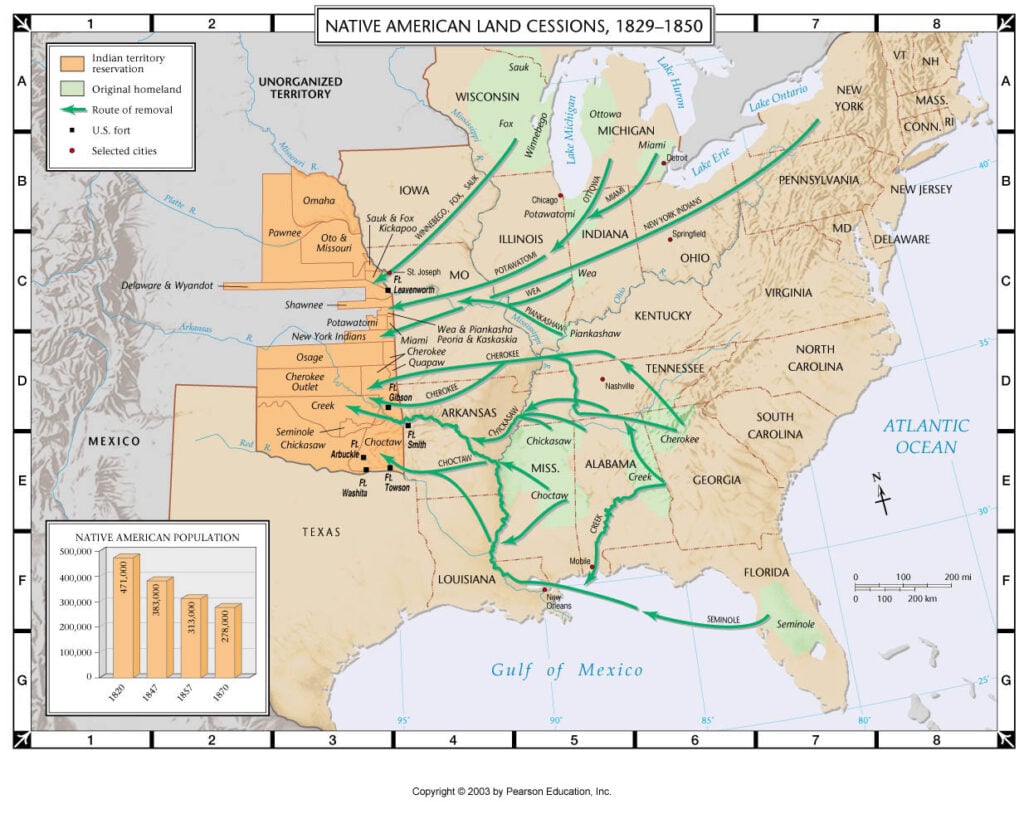

While the Huron Potawatomi, and other Potawatomi, generally maintained peaceful relations with their new non-Indian neighbors, the increased pressure from settlers, many of whom illegally entered Indian lands, often resulted in violent conflict between settlers and the resident Indian tribes. The solution championed by Andrew Jackson and others in the U.S. Government became the nineteenth-century policy referred to as "Indian Removal," by which Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River would be encouraged to sign treaties giving up the remainder of their lands and be relocated to lands west of the Mississippi.

Unfortunately, the Nottawaseppi Reservation was a momentary home in Michigan. In the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, signed September 26, 1833, the Potawatomi (including the Nottawaseppi Huron Band) ceded the Nottawaseppi Reservation and other lands located in Michigan to the United States. The treaty required the Potawatomi to remove west to new reservations in the Kansas Territory. Consequently, the U.S. Government ordered an involuntary removal of nearly every band of Potawatomi to Kansas by 1838.

“Young John” Moguago, son of "Old" Moguago and grandson of Mogoagon, emerged as the head chief of the band upon the death of Sau-au-quett.

On October 15th, 1840, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi forcibly began their long trek to a reservation in Kansas.

In the spring of 1842, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi returned to the Nottawaseppi Prairie.

Between 1845-1848, a number of NHBP members, estimated to number between 40 to 60 persons, pooled 120 acres of land was purchased with annuity money owed to the “Potawatomi of Huron” from the 1807 Treaty of Detroit with the U.S. Government and used this money to purchase 120 acres of land.

During the mid to later 1840's, the Pine Creek settlement experienced the beginnings of Methodist missionary activity. The resulting founding of a church at Pine Creek would do much to shape the settlement for the next century.

John Moguago died in 1863. He was buried on the reservation cemetery with his grave marked in the traditional manner by an oak tree (still standing as of 2018). The position of Chief was transferred to his uncle, "Old" Pamptopee and then a year later, in 1864, to Phineas Pamptopee.

In 1889, the $400 annual annuity the NHBP had been collecting since 1845, from the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, was compounded for a lump sum. Individual tracts of land were purchased, resulting in the establishment of East Indiantown.

Between 1900 and 1930, the NHBP saw a gradual population increase, which can be directly traced to the control of childhood diseases such as diphtheria and measles and the gradual extermination of tuberculosis in the adult population

This Taggart Roll is considered the “base roll” for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi’s present Tribal membership; present members must show that they descend from persons listed on the Taggart Roll.

During the years between 1904 and World War I, many of the families who had bought land in the East Indiantown area sold the property. The settlement again became primarily focused on the original Pine Creek 120 acres and a new town, about two miles from the old settlement.

Phineas Pamptopee, who had been chief for 50 years, died in 1914. The selected chief for the next ten years was his youngest son, Stephen Pamptopee.

The strong influential role of Samuel Mandoka within the Pine Creek settlement began during the lifetime of Steven Pamptopee. At Steven’s death in 1926, Samuel was not formally designated to the “office” as chief but was essentially appointed by consensus of the residents of the Pine Creek Reservation because of his good education and outgoing personality.

The relative prosperity of the settlement in the later nineteenth century fell prey to the general agricultural decline of the post-World-War-I era and was intensified by the Great Depression.

The Indian Reorganization Act (“IRA,” “Wheeler-Howard Act”), signed June 18th, 1934, was intended to encourage tribes to assume more control of their governance and help change the aforementioned “fundamental impracticabilities of law,” which was resulting in so many problems in Indian Country. The press signaled this act as an "Indian New Deal" program; it provided tribal participants assurances that their land would be held forever in Federal trust and that eligible tribes could develop their economies. Albert Mackety, Levi Pamp, and another NHBP member, Austin Mandoka, who was Chairman of the Athens Indian Committee, learned of the IRA and believed the legislation could benefit the community.

Albert Mackety and Levi Pamp provided the key political leadership of Pine Creek for the next 40 years.

Some NHBP members joined the armed services during World War II, while others took jobs in urban industries. During these years, several men worked in factories in Battle Creek or Detroit; women also took industrial jobs.

After World War II, the pattern of work off the reservation continued to grow. For many of the NHBP, this period marked the first participation in the urban labor market. By the end of the War, factory employment and other urban jobs had largely replaced the earlier dependence on seasonal farm work and subsistence farming.

By 1960, most of the group's members were no longer living at Pine Creek but had moved to cities in southern Michigan that provided employment opportunities. Continuing a trend to seek off-reservation employment that had begun in the 1940s, more and more of the young adults moved out of the core geographical area centered at Pine Creek. The dispersal resulted from a rapidly increasing birth rate which caused significant population pressure on the limited Pine Creek land.

The decade of the 1970's proved to be a pivotal period in the development of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi’s political organization.

In the spring of 1972, the NHBP decided to make their first concerted effort since 1934 at seeking federal reaffirmation. This effort continued for several years with little progress despite considerable effort.

Between 1980 and 1986, one major focus of HPI’s efforts was the preparation of the Federal acknowledgment petition for consideration under a new administrative process established under regulations adopted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Those regulations required tribes, whose government-to-government relations with the United States had been improperly terminated, to submit documentation that confirmed that their tribe had continued to exist as a distinct government from treaty times to the present.

On December 19, 1995, the United States government restored “federal recognition” to the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi. Federal reaffirmation was a defining point in the NHBP history and the Pine Creek Reservation. It acknowledged a unique and interconnected group of people, allowing access to needed government programs unavailable to non-recognized tribes. This access stimulated a period of home and infrastructure construction. Today the reservation is bustling with activity and is becoming a showcase community.

The NHBP has accomplished a great deal since federal reaffirmation in 1995. The Pine Creek Reservation has become a secure homeland quickly developing into a first-class Tribal community with a beautiful Government Center, Department of Public Works, Community & Health Center, energy-efficient homes, and Justice Center. Education, health, housing, and environmental programs continually strive to improve the Tribe’s quality of life. Despite these recent developments, the Reservation still retains its rural flavor, with unspoiled forests, fields, and Pine Creek as a backdrop.

After more than 10 years of planning, strategy, and vision, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi opened the doors to FireKeepers Casino on August 5, 2009.

Waséyabek Development Company, LLC (WDC) is a 100% Tribally-owned holding company that manages the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi’s non-gaming economic development activities.

In 2021, the Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Departments (CMTED) created the first edition of a resource manual to accompany the 2019 Michigan State Board of Education Social Studies Standards Guide. The “Manifesting Destiny: Re/presentations of Indigenous Peoples in K-12 U.S. History Standards,” study found that prior to 2019, none (zero) of Michigan’s 39 standards mentioned Indigenous Peoples or life post-1900. This finding speaks to the longstanding historical practices that have attempted to erase the histories of the Anishinabek people and continue to confine Indigenous Peoples to a distant past. These new standards are a significant improvement over the old, as they now contain 51 standards that reference Indigenous Peoples and 25 of them are post-1900.