Figure 12. “The Signing of the Treaty of Greene Ville,” by H.C. Christy, 1945. [Oil-on-canvas]

Signed August 3rd, 1795, the Treaty of Greenville followed negotiations after the Native American loss at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. This defeat ended the ten-year-long Northwest Indian War and established the Greenville Treaty Line, which for many years became a boundary between territory that was acknowledged as remaining under the sovereign authority of various Native American tribes and had been ceded by tribes to the United States government that was open to European-American settlers.

Signed August 3rd, 1795, the Treaty of Greenville followed negotiations after the Native American loss at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. This defeat ended the ten-year-long Northwest Indian War and established the Greenville Treaty Line, which for many years became a boundary between territory that was acknowledged as remaining under the sovereign authority of various Native American tribes and had been ceded by tribes to the United States government that was open to European-American settlers.

The Native American tribes involved in this treaty ceded a significant area of modern-day Ohio, the future site of downtown Chicago, the Fort Detroit region, and the Maumee and lower Sandusky area in exchange for “a quantity of goods to the value of twenty thousand dollars,” including an annuity of $9,500 in goods to be divided into set proportions amongst each of the twelve tribes present at the signing (Kappler, 1904, p. 2). The goods that were offered as part of the annuity were “domestic animals, implements of husbandry [for agricultural purposes], and other utensils convenient for them” (Kappler, 1904, p. 2).

Native American leaders who signed the Treaty included chiefs of several Potawatomi bands, including Potawatomi Chief White Pigeon and Potawatomi Chief The Sun. Also signing the Treaty were leaders of the following tribes: Wyandot (Chiefs Tarhe, Leatherlips, and Roundhead), Delaware (Lenape; several bands), Shawnee (Chief Blue Jacket), Ottawa (several bands), Chippewa, Miami (Chief Little Turtle; several bands), Wea, Kickapoo, and Kaskaskia.

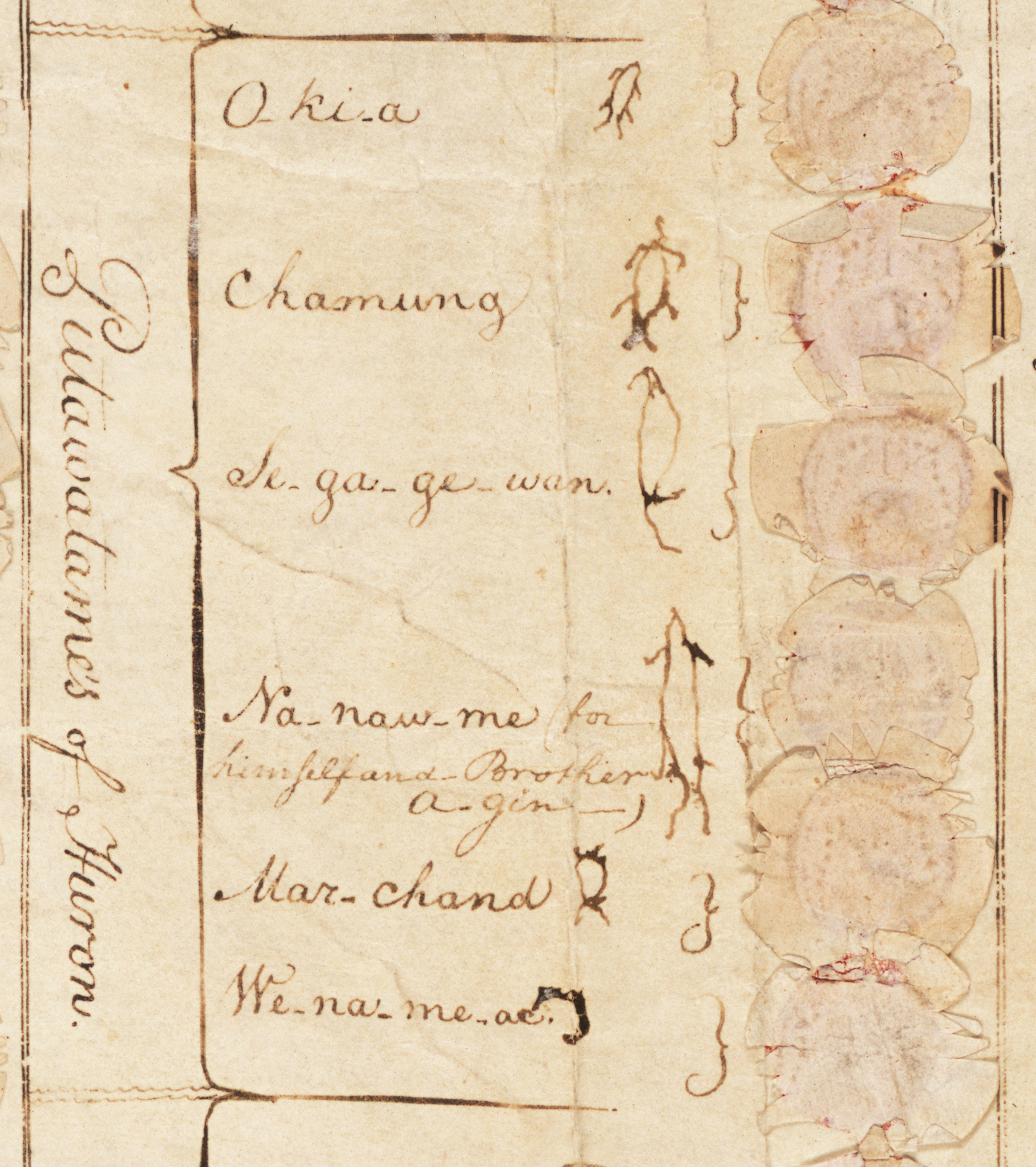

The United States government recognized the governmental/sovereign status of the Huron Potawatomi in multiple treaties during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; the first being the Treaty of Greenville (1795).

While the Treaty of Greenville was intended as a Peace Treaty that protected Indian lands from incursions by settlers, it precipitated a 45-year period during which the Potawatomi Bands in lower Michigan ceded (sold) their land to the U.S. Government for as low as 1.2 cents per acre (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 247). The last of these treaties was the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which authorized the forced relocation of the Potawatomi to Kansas by the U.S. Army.

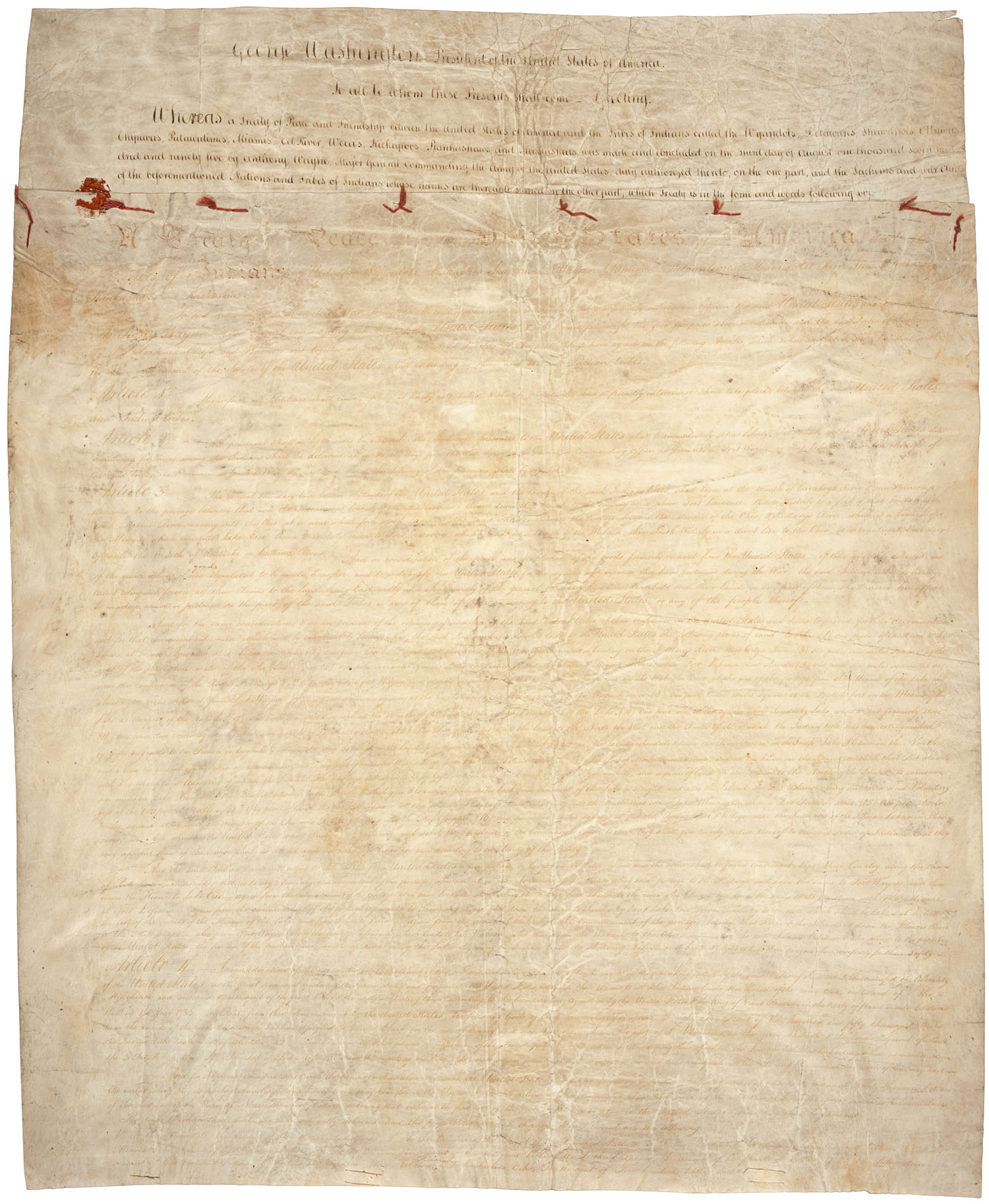

Figure 13. Treaty of Greenville, Page 1. From “Treaty of Greenville, August 3, 1795 (Ratified Indian Treaty #23, 7 STAT 49), between the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomie, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Ka,” 1795, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, p. 1 (https://digitreaties.org/treaties/treaty/299800). In the public domain, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

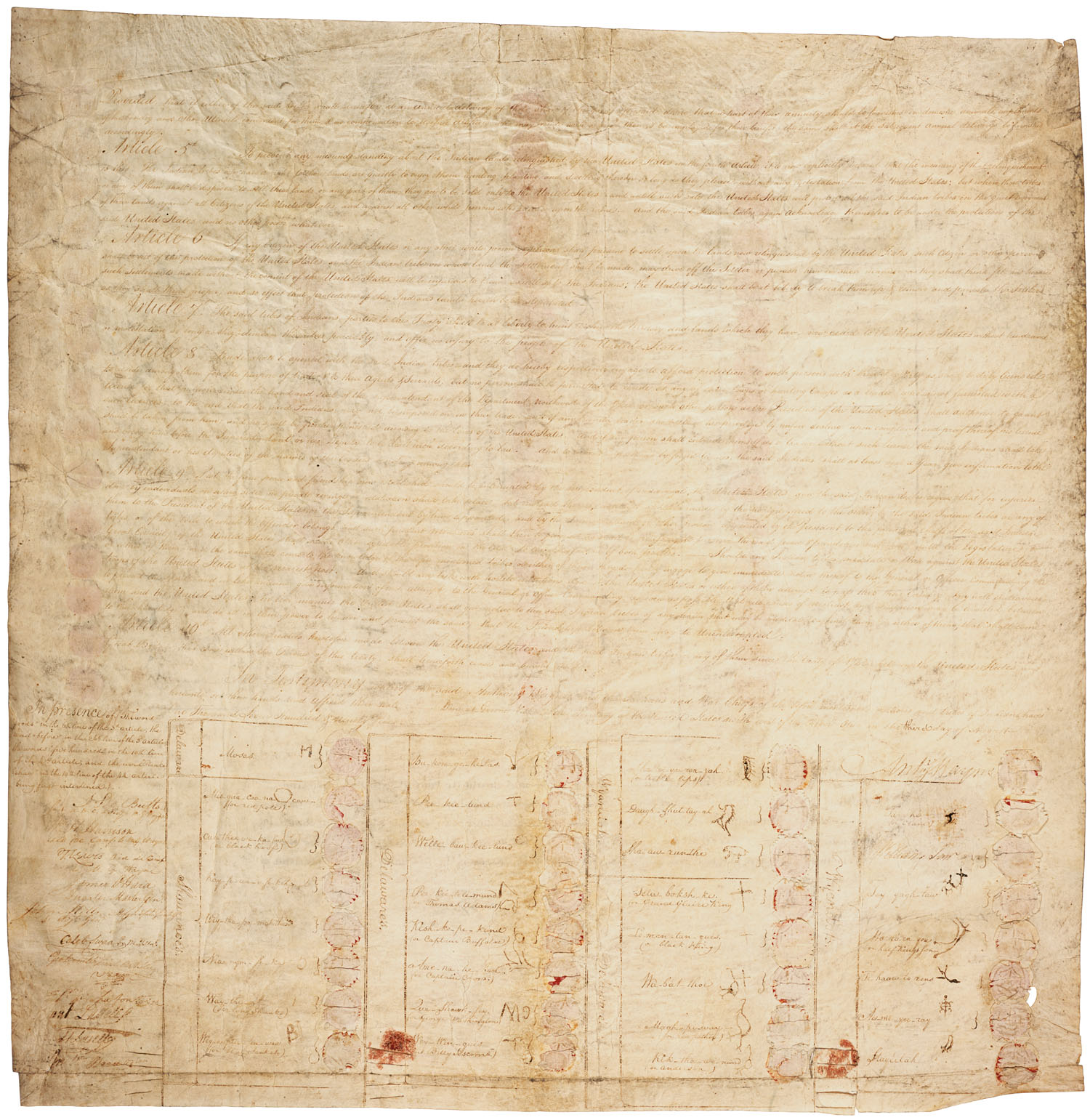

Figure 14. Treaty of Greenville, Page 2. From “Treaty of Greenville, August 3, 1795 (Ratified Indian Treaty #23, 7 STAT 49), between the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomie, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Ka,” 1795, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, p. 2 (https://digitreaties.org/treaties/treaty/299800). In the public domain, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

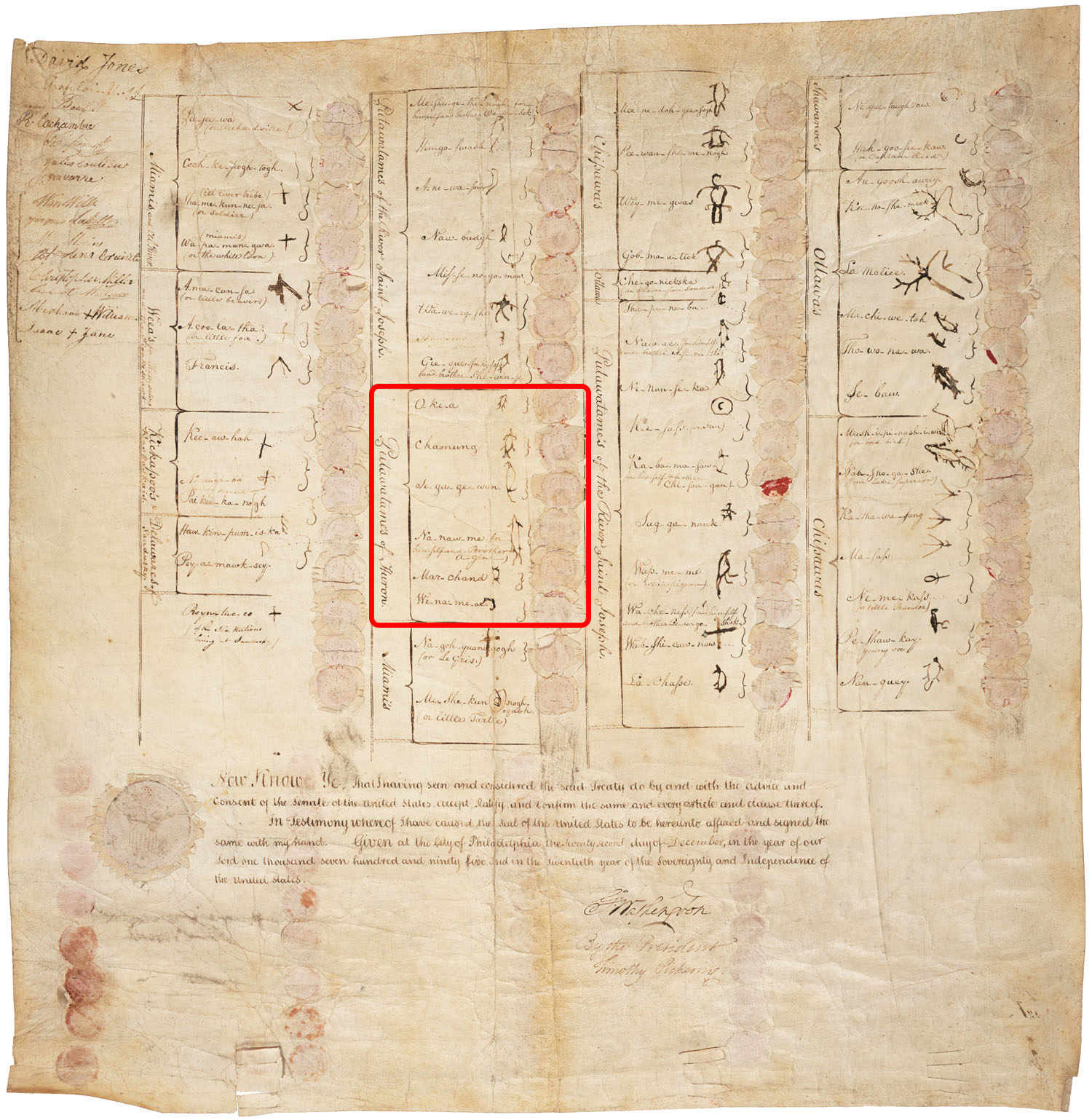

Figure 15. Treaty of Greenville, Page 3. From “Treaty of Greenville, August 3, 1795 (Ratified Indian Treaty #23, 7 STAT 49), between the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomie, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Ka,” 1795, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, p. 3 (https://digitreaties.org/treaties/treaty/299800). In the public domain, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

Figure 16. Potawatomi of Huron Signatures. From “Treaty of Greenville, August 3, 1795 (Ratified Indian Treaty #23, 7 STAT 49), between the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomie, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Ka,” 1795, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, p. 3 (https://digitreaties.org/treaties/treaty/299800). In the public domain, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

References:

Christy, H. C. (1945). Signing of the Treaty of Green Ville [Oil-on-canvas].

Kappler, C. (Ed.). (1904). The Treaty of Greenville 1795. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Vol II (Treaties). https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/greenvil.asp

Treaty of Greenville, August 3, 1795 (Ratified Indian Treaty #23, 7 STAT 49), between the Wyandot, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomie, Miami, Eel River, Wea, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Kaskaskia Tribes (Indian Treaties, 1789-1869). (1795). U.S. Government; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11. https://digitreaties.org/treaties/treaty/299800/

Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc. (1995). United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Branch of Acknowledgement and Research. https://www.bia.gov/sites/bia.gov/files/assets/as-ia/ofa/petition/009_hurpot_MI/009_pf.pdf